Now here’s an example of the bad postmark being 100% my fault. You may remember the Toy Story card I had discussed earlier. I really loved this assembly, since the Gene Autry stamp and the earlier science fiction stamp matched Woody and Buzz Lightyear perfectly.

I was incredibly surprised when the USPS issued two sets of

Pixar stamps, though. And when the first

set came out with a set of 5 that included Buzz but not Woody, I knew Woody

would be in the subsequent year’s issue.

So, now was an opportunity to get both on the face of the postcard, too!

Big Mistake. As you

can see, what was previously a wonderful looking postcard now is now an ugly,

cluttered mess. Part of the reason is

the trend of the USPS of having their illustrated postmarks be much wider and

denser with the ink.

But the larger failing was mine. The card would’ve been much better with the

two separate Pixar cancellations on the back of the card, but the thought of

having them both on the front was too irresistible, and what resulted in the

long run is a big old garbled mess. You

can still make the images out, but the impact of the first combo of stamps is now

mostly lost.

When the Quilts of Gee’s Bend issue came out, this stamp worked

uncannily well. Using it was a

no-brainer. So when Sinatra came out two

years later, where should I put it?

Logic dictated the front but I couldn’t think of anywhere it could go

without losing the effect from the previous stamp. So I did this instead:

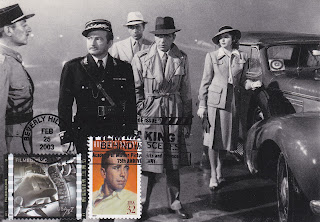

Putting the Sinatra stamp on the back meant I could add the drug abuse stamp without it cluttering things up further (Otto Preminger’s 1955 film was one of the first major Hollywood productions to deal with the subject). Later, when the Jazz stamp came out, I added it to the reverse, too.

I’ve made other similar judgment calls on both sides, but while I’m glad I have a scan of what it looked like before, the Toy Story example is the one I still regret the most.

Buzz and Woody are Scott #s 4555 and 4680 respectively. Sinatra is Scott # 4265, the Prevent Drug Abuse stamp is # 1428, and the Jazz stamp # 4503.