The 1982 Oscar race is the first one I can remember. Not only were 3 of the Best Picture nominees

films that I’d seen (a first for my then 12-year-old self), but other films I’d been

allowed to see—Annie, TRON, Poltergeist—were in the running in some of the smaller

categories, too. Only years later would

I catch some of the other highly-acclaimed nominees like Missing, The Verdict, Sophie's Choice or Das Boot.

But that year, it was all about Gandhi and Tootsie and E.T.:

The Extra-Terrestrial, a poster of which hung on my bedroom wall, another first

(previously it had all been sports legends and super heroes but never

movies). These were the 3 top nominated

films—with 11, 10, and 9 nods respectively—and the anticipation was high to see

who would emerge the winner in the end.

But what I do remember about the race in the build-up to the

nominations—and eventually the ceremony itself—was the talk about the

gender-bending that year, for not only was Dustin Hoffman’s masquerade as a

woman in the mix, but so was Julie Andrews (whom I only knew as Mary Poppins

and Maria Von Trapp) as a woman playing a man playing a woman in Victor Victoria and John Lithgow (a supporting actor nominee) as a transsexual in The World According to Garp. In the end,

none of them would win, but it was the first time I remember the Academy Awards

acting as a springboard for conversation that intersected with the cultural

zeitgeist.

Looking back, it seems almost a miracle that a movie almost

exclusively about Muslims, Hindus and the tyranny of white imperialism was even

made, let alone go on to sweep with 8 wins.

But few people talk about Gandhi now, except for the role it played in

catapulting Ben Kingsley (the Best Actor winner) into our consciousness. E.T. is still adored, though Spielberg’s

career has expanded well beyond the summer blockbuster wunderkind which was his

reputation (not without a bit of condescension) 35 years ago.

But

Tootsie has taken on a new, burnished reputation as one

of the Great American Comedies, even elevated to #2 of all-time by the American

Film Institute in 2002 (behind only

Some Like It Hot, another

guys-in-gals-clothing romp).

But to

these eyes, time has not been kind to Sydney Pollack’s film and while it still

has some very funny moments, it’s not without the acrid aftertaste of its

regressive, even toxic, views on sex and gender.

This is especially true when compared to

Blake Edwards’s

Victor Victoria, which is just as funny but also far more

compassionate, generous, and forward-thinking.

Tootsie is about Michael Dorsey, a New York actor who’s

earned a well-deserved reputation as a prima donna, but whose vanity is rooted

in his adherence to the “craft” of acting, which he uses as an excuse to be

insulting, unyielding, and a royal pain-in-the-ass. This renders him unemployable and the only

way he can get a job is to impersonate a woman at an audition, which lands

him a gig on a daytime soap opera, Southwest General.

Victoria Grant is also hard on her luck. A classically-trained singer in 1930s Paris,

she is destitute and desperate and can only find work by taking on the guise of

Count Victor Grazinski, a gay Polish aristocrat and female impersonator. In both films, the only other people complicit in these actors’ secrets are their roommates (Bill Murray and Oscar-nominee Robert

Preston, respectively). And both find

their love lives and worldviews altered from the experience.

Tootsie is on the surface an exercise in empathy. Michael has to experience firsthand the

indignities of harassment at work, the condescension of the piggish male

director (Dabney Coleman), the misogyny of playing roles that only perpetuate

stereotypes, and the countless everyday challenges (hailing a cab, buying endless

accessories) that women face. In this

sense, the film actually works fairly well.

The problem is the film isn’t satisfied with him as a low-level actress

who gets to walk a mile in another’s high heels. For the movie’s purposes, “Dorothy Michaels” has

to become a feminist icon. She talks

back to the director, changes her lines on the show without permission, and is

never really reprimanded or punished like any woman would be in such a sexist

environment. Instead, she’s indulged and

rewarded, with a fervid fan base and photo shoots for the covers of Woman’s Day

and Ms. It’s a fantasy of male

privilege—a world where the women are brow-beaten or complacent and where it

takes a guy to come to the rescue and role model real feminism, even if he has to

dress up as a gal to do it.

What’s worse is that there’s no evidence that Michael has

learned anything from his parallel life to inform his “real” one. His treatment of his friend and pseudo-lover

Sandy (a delightful, Oscar-nominated Teri Garr) is atrocious, he makes sexual

advances to his co-worker Julie (Supporting Actress winner Jessica Lange) as

both a man and a woman, and when he finally “outs” himself as a dude, he still

feels entitled to approach Julie on the pretense that they were “good friends”

the entire time she was confiding in him while he was lying to her. And she falls for it! Another male privilege fantasy. While perhaps slightly more enlightened when

wearing a girdle, Michael hasn’t really changed. He still gets his way through coercion and

egoism but we’re supposed to believe that he’ll somehow be different than Julie’s

malignant previous boyfriend. Lange’s

portrayal only scratches the surface of how damaged Julie is, but she’s clearly

co-dependent and he’s a narcissist who, lip service aside, is still lacking in

any real self-awareness.

Victor Victoria, on the other hand, is about real female

empowerment, as Victoria becomes aware of the choices and privileges she gets

as a “man” that she wasn’t even aware of previously. But more than that, the film embraces sexual

identity and the variety of ways it expresses itself. Sex (the act) is only seen in relationship to

power in Tootsie. But the complexity of

desire and the fluidity of attraction is explored in smart, sophisticated ways

in VV. This is particularly true with

the character of King Marchand (James Garner). He’s initially attracted to Victoria before he

discovers that “she” is a drag act. But

even then, his curiosity is piqued—as well as his suspicions—and they are all

tied to what he as a man is traditionally drawn to. After Victor's debut, King confronts "him" backstage.

King: I find it

hard to believe that you’re a man.

Victor: Because you

find me attractive as a woman?

K: Yes, as a

matter of fact.

V: It happens

frequently.

K: Not to me.

V: It proves

the old adage, “There's a first time for everything.”

K: I don’t

think so.

V: But you’re

not 100% sure.

K: Practically.

V: But to a man

like you, someone who believes he could never under any circumstances find

another man attractive, the margin between “practically” and “for sure” is as

wide as the Grand Canyon.

K: If you were

a man, I’d knock your block off.

V: Then prove

that you’re a man.

K: That’s a

woman’s argument.

V: Your

problem, Mr. Marchand, is that you’re preoccupied with stereotypes. I think it’s as simple as you’re one kind of

man. I’m another.

K: And what

kind are you?

V: One that

doesn’t have to prove it—to myself or anyone.

Later, after he learns her secret and they spend the night

together, King wants her to quit the show and revert back to being Victoria. But she refuses, noting the hypocrisy of

asking her to do something he would never consider doing himself. She recognizes the power, and freedom, that has come with her new standing and is loathe to lose it. The two then begin to see each other

romantically, but since “Victor” must continue to maintain his public identity,

King is put in the position of being perceived as gay, even though he knows

he’s not. In Tootsie, there are several

scenes that are played for comic effect about characters being mistaken for

being gay, but it never extends beyond a joke.

But VV mines this landscape for larger truths about homosexuality and society’s

scrutiny, personal worth vs public perception, and ultimately accepting

yourself with or without others’ validation.

So many of the supporting characters feed and reflect this

theme in different ways.

King’s moll

Norma (hilarious, Oscar-nominated Lesley Ann Warren) can’t decide whether to be

jealous or not as Victor slowly insinuates himself into King’s orbit.

King’s bodyguard Squash (Alex Karras) comes

out to his boss as gay after he mistakes his boss for also swinging that way—a

genuinely touching moment layered under a light comic affect.

And then there’s Robert Preston’s Toddy.

I certainly can’t begrudge Louis Gossett

Jr.’s Supporting Actor victory that year for

An Officer and a Gentleman (the

first person of color to win that award).

But Preston’s performance is one of the finest in any musical ever—a

queen who’s funny, catty, nosy, flirtatious, but also has the biggest heart in

the film.

He’s sublime.

Of course up to this point, nobody had ever

won an Oscar for playing a gay character (the first would be William Hurt in

Kiss of the Spider Woman three years later) and it’s impossible to say if

Hollywood’s old-school homophobia played a part in Preston losing, but it

certainly wouldn’t surprise me.

This was

his only nomination (incredibly, he was overlooked for

The Music Man 20 years

earlier), and he’s perfect.

Then again, it’s hard to think of a mainstream film from the

80s that’s as gay-friendly as Victor Victoria.

Maybe having it set as a European period piece, and a musical no less,

helped. But it features a wide variety

of queer characters as part of the natural fabric of the cabaret scene (and beyond)

and even has a remarkable musical number that explicitly references the duality

of masculine and feminine in everyone.

The fact that the central romance is hetero doesn’t relegate the LGBT

themes to the margins. They’re still unquestionably

front and center and make the movie feel, even a third of a century later, very

modern. By contrast, there isn’t a

single gay character in Tootsie’s NY acting community that we see. The closest concession we get is a brief

cameo by Andy Warhol.

Victor Victoria plays broader and indulges in familiar

tropes of farce (especially with Edwards’s impeccable ballet of characters

hiding in closets and on balconies), but it’s also far more real and human in

the long run. Tootsie has some

undeniably funny moments, but it’s all in the service of reinforcing narrow

sexual roles and having things revert back to comfortable normalcy. Whatever happens to Sandy, who gets such

short shrift? That the movie forgets her

(the most complex and believable woman in the film) says everything about the

narrative’s priorities. Lange may have

won the Oscar, but Garr’s Sandy is the conscience of the film and gets

steamrolled for her efforts. In fact,

all of the Grrl Power moments are via Hoffman and the film seems to delight In

how fickle or hypocritical its female characters are. It’s at its core a surprisingly mean movie, while VV is an

open-hearted, nonjudgmental one.

Blake Edwards holds two unique records in Oscar history. No director has had his films earn as many

nominations (33 total) without ever earning a Best Director nod himself. His only career nomination was for VV’s

screenplay, and while he did lose (to Missing), he would earn an Honorary Oscar

from the Academy before passing away in 2010.

The other Oscar record is that no director’s films earned more nominations for

Best Song than his: 8 total, all with the assistance of Henry Mancini, his

longtime collaborator. Mancini won 4

Oscars, all for Edwards movies—2 for Best Score (Breakfast at Tiffany’s and VV)

and 2 for Best Song (“Moon River” from Breakfast and the title tune from The

Days of Wine and Roses).

Sydney Pollack lost Best Director that year to Richard Attenborough, but would go on

to win it three years later for Out of Africa.

Still, the best thing about Tootsie is his acting, as Michael’s long-suffering

agent, George. He’s amazing and

incredibly funny and if I had to choose Pollack’s filmography as director or as

actor (which includes fantastic turns in Michael Clayton, Eyes Wide Shut, and

Husbands and Wives), I would pick the latter.

His one scene in Death Becomes Her is a masterclass in comedy and

funnier than the rest of the movie combined.

He died in 2008.

Some other trivia odds & ends about the 1982 Oscars:

·

Jessica Lange became the second person in

history to receive a Lead and Supporting nomination in the same year for

different films (the first being Fay Bainter over 40 years earlier). She was up for the lead in Frances and this

double-whammy no doubt had some bearing on her winning for Tootsie, the only

Oscar that film would get.

·

Charles Durning, who played Jessica Lange’s dad

(and Dorothy Michaels’s suitor) in Tootsie was also nominated for Best

Supporting Actor that year, but for The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, a

title which included a word that went over my head in 6th grade.

·

This year’s sequel to

Blade Runner reminds us

that Ridley Scott's original quite famously lost both of its nominations back in 1982,

most notoriously for Visual Effects to

E.T. (for more thoughts on the Spielberg film, check out

my blog post here).

·

In 1982, Das Boot became the first foreign

language film to earn six Oscar nominations, and its director Wolfgang Petersen still holds an Academy record himself: Director whose films have earned the most

nominations (15 total) without winning anything at all.

·

Mickey Rooney received an Honorary Oscar at that

year’s ceremony, making him the only person in Academy history to win both a

Juvenile Oscar (a miniature statuette they gave to young performers for a short

time) and a full-size one.

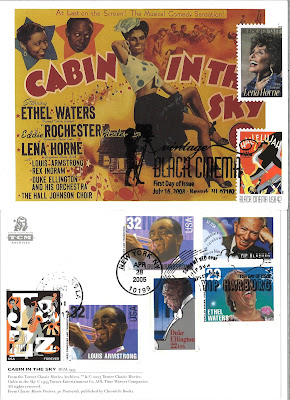

Since this blog also covers postage stamps in the movies,

both Tootsie and Victor Victoria have items worth mentioning. Southwest General’s producer (Doris Belack) says that the

show is getting 2000 letters a week thanks to Dorothy (whose character's name is Emily Kimberly), and we see a shot of

some of these letters, which feature real-life stamps including the floral

Love stamp (Scott #1951) and the fire pumper stamp (#1908), both issued in

1981. As for VV, there are no stamps

visible, but the Parisian set was built on a soundstage, including this

storefront for “Timbres Poste” (French for postage stamps).

As for the cards from my collection, the Henry Manicini

stamp (which includes Victor Victoria in the titles listed, if you look close

enough) is Scott #3839. Audrey Hepburn

is #3786 while the two Tiffany stamps are #3757 and #4165. The Han Solo stamp is #4143l and while

Tootsie wasn’t nominated for Best Makeup (only the second year of that category’s

existence), I did include a Makeup stamp (#3772e) from the American Filmmaking

series. The "Things to Come" stamp is from

the UK, released as part of a science fiction set in 1995.