Of all the MGM musicals ever made, spanning over

half-a-century, only 2 have been memorialized on a US postage stamp. One is, unsurprisingly, The Wizard of Oz,

which I have discussed on this blog before.

The other? Not any of the usual

suspects, like Singin’ in the Rain or The Band Wagon or Meet Me in St.

Louis. The only other film is King

Vidor’s Hallelujah (1929).

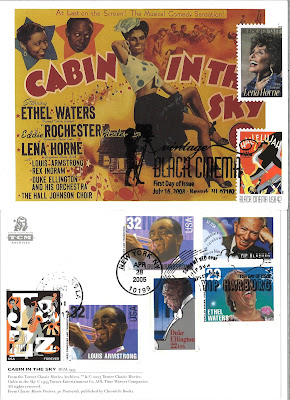

That was part of a 5-item postal issue on early Black Cinema

(also discussed in an earlier post) and Hallelujah is easily the most famous of

the 5, and a seminal work in the genre because even with sound in the movies

less than 2 years old, you can see Vidor pushing the aesthetic envelope. There’s certainly a lot to dissect about the

film, from its ground-breaking origins (it was one of the first Hollywood

studio films with an all-black cast) to its troubled legacy because of the

narrative it helped fuel about African-American stereotypes.

But something that makes this film stand out among musicals

is also something it has in common with another all-black MGM musical 14 years

later, Vincente Minnelli’s Cabin in the Sky (1943). And that’s the unique role that religion

plays in both films. For integral to

both films’ messages is the ways church and God, music and ritual are

hard-wired into black culture.

Hallelujah is about a sharecropping family whose eldest son Ezekiel

(Daniel L. Haynes) gets lured into assorted temptations (gambling, women) and

it’s his religious rise as a rabble-rousing pastor and eventual fall from

grace, a victim of his vices, that comprise the backbone of the film. Throughout, we see that singing—in the cotton

fields, with neighbors, in church and nightclubs—is an important part of the

family’s life. Musicals have often been

criticized for being “unrealistic” in having their characters spontaneously

burst out in song, but in Hallelujah, it feels completely normal because song

and community are intimately entwined.

Music brings people together, providing inspiration and comfort in a

hard-scrabble life and so all the music numbers have an almost naturalistic

feel—both the traditional spirituals but also the ones written for the film

(most notably “Waiting at the End of the Road”, by Irving Berlin).

Cabin in the Sky is actually pretty similar in that Joe

(Eddie “Rochester” Anderson) has his soul fought over by competing angels and

demons as he is also tempted by gambling and women and faces a troubled path

toward redemption that isn’t without its own pitfalls and distractions. While Hallelujah is presented as melodrama

and cautionary tale, Cabin is played for laughs and uplift, but it also has

musical numbers that take place in the wide array of African-American centers

of community: church, juke joints, backyards and work gangs. Here, the musical heavy lifting is done by the

marvelous Ethel Waters, who sings the title tune as well as the Oscar-nominated

“Happiness Is a Thing Called Joe” (by Harold Arlen and E.Y. “Yip”

Harburg). But she gets tons of great

support by Lena Horne and cameos from Louis Armstrong (as a demon) and Duke

Ellington.

But it’s interesting that when you look at the films, the

churches act as spiritual centers and this is in sharp contrast to decades of

mainstream Hollywood musicals that rarely use churches as much more than

narrative devices. Ezekiel whips his

camp meeting congregation into a religious fervor, and while his personal story

is one of backsliding and hypocrisy, the message of love and confession is one

that touches a nerve in his flock (and which is upheld without irony by the rest

of his revivalist family). Joe’s

afterlife in eternity is genuinely at stake and fidelity and responsibility are

depicted as paths toward a better marriage and better living. The square Rev. Green (Kenneth Spencer) may

not be nearly as fun as Rex Ingram’s hilarious Lucifer, Jr., but he has Joe’s

best interests at heart—not just to follow a set of prescribed rules but to

improve Joe’s relationship with the devoted Petunia (Waters).

I’m hard pressed to think of many examples of the great

canon of American musicals pre-1970 that touch on central religious themes that

way. Sure, churches are abundant for

social gatherings or weddings (“What a Lovely Day for a Wedding” from Royal

Wedding or “Get Me to the Church on Time” from My Fair Lady). Bible stories are alluded to in song lyrics,

from Seven Brides for Seven Brothers’ “Sobbin’ Women” to Elvis singing “Hard

Headed Woman” in King Creole. But

they’re little more than plot points, without any larger thematic

resonance. Heck, even Bing Crosby as a

priest in Going My Way is rarely a fount of theological insight but rather a source of

warm, friendly, homespun advice. Ditto

the nuns in The Sound of Music.

Which make Cabin and Hallelujah interesting to me, since

they aren’t afraid to immerse themselves in the middle of a part of the

American social fabric that most musicals are reluctant to touch. Those other films may implicitly embrace what

some might consider religious “values”, but Hallelujah explores the complex

relationship between faith and character, and Cabin finds joy in spaces that

can be both reverent and rambunctious.

Once the 70s kick in, we see stage adaptations like Fiddler on the Roof

or Jesus Christ Superstar that more explicitly examine (and question) beliefs

and traditions, but these early MGM musicals not only paved the way in bringing

African-American casts and culture front-and-center to white audiences, but its

worship sensibility, too.

Now, I did mention that only 2 MGM musicals have been

depicted on a USPS stamp, but I should make a technical concession to Show Boat

(1951, Sidney) for while the film itself is not on a stamp, the original

Broadway musical is.

Hallelujah was released in time for the 2nd

annual Academy Awards, and it was King Vidor’s second Best Director

nomination. He would earn five in his

career—a record number in that category for someone who would never earn a competitive one. He did receive an Honorary Oscar in 1978. His nomination for Hallelujah is unusual in

that the director nomination was the only one the film received. This has only happened a handful of other

times since: The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, Alice’s Restaurant, Blue Velvet,

The Last Temptation of Christ, Short Cuts and Mulholland Dr.

Cabin was Minnelli's first feature film, and he would go on to helm two Best Picture winners that

were MGM musicals: An American in Paris and Gigi, the latter earning him a Best

Director statue, too.

For more entries in this weekend’s MGM musical blogathon, go

here.