My first associations with Fred Astaire were with

Christmas. One of the first films I

remember him starring in was the family-friendly TV movie The Man in the Santa

Claus Suit (1979), where he is an ever-present holiday sprite in NYC as three

different men find unlikely solutions to their respective problems through a

Santa suit they rent from Fred. Of

course, there was the ubiquitous Holiday Inn (Sandrich/1942), which first introduced the

song "White Christmas" (sung by co-star Bing Crosby). But the earliest thing I remember was the

Rankin-Bass Christmas special Santa Claus Is Coming to Town, narrated by Fred, which

first aired in 1970, the year I was born.

Rankin-Bass, of course, were the producing pair (Arthur

Rankin Jr. & Jules Bass) who created a series of animation specials, mostly

Yuletide but other holidays too, that were prevalent when I was growing

up. Quite a few used puppets and stop-motion,

including the first, 1964’s Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer, which received a

postage stamp issue last year. That’s an

origin story for Rudolph, with Santa an established character and Burl Ives (as

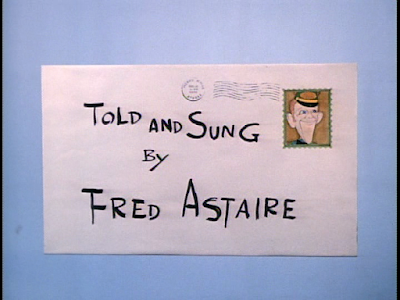

a North Pole snowman) acting as singing narrator. SCIC2T follows the same template, with Fred a

mailman who uses the letters from Santa he encounters as a springboard to

explain Kris Kringle’s backstory. He

makes a terrific storyteller and even sings the title tune, a bonus pleasure.

Like Gene Kelly, the other legendary male dancer from

Hollywood’s Golden Age, Fred Astaire doesn’t have a US postage stamp yet. It’s always curious how the decision-making process

is conducted for which film stars get memorialized by the USPS, either in the

Legends of Hollywood series or an offshoot issue. Certainly, he’s a profoundly influential

figure in popular culture, both as singer & dancer, and while Bing has a

stamp, as do Fred’s co-stars of the classic musicals Easter Parade (Judy

Garland) and Funny Face (Audrey Hepburn), he's still waiting for one.

Fred’s only Oscar nomination was for the very unmusical The Towering

Inferno (Guillerman/1974) and his co-star there, Paul Newman, also has a stamp.

In fact, the closest thing to a postage stamp in the US that

Fred has is actually in his Rankin-Bass Xmas special, where all the credits are

formatted as postal letters, with the characters depicted as stamps.

Though no longer mainstays on network TV, these specials

still get rotation in December on other cable channels, like ABC Family. Perhaps their best facet were the songs,

which had nice memorable little hooks.

But revisiting Santa with my mom recently, I noticed something unusual:

they cut one of the tunes, and a rather central one, since it’s the musical

motif for Santa himself (whose theme recurs throughout the show). The internet being what it is, it was easy

enough to find the missing song, which has the following lyric, sung by Kris:

If you sit on my lap today,

A kiss, a toy is the price you pay.

When you sit on my left knee, don’t be stingy.

Be prepared to pay.

While the song itself is innocently karmic (the love you

give comes back to you), the quid pro quo aspect of coercing affection with the

promise of gifts sends a very different message these days.

It’s also interesting that Kris and the future Mrs. Claus

(the gorgeous redheaded school marm, naturally) are also essentially a common

law union, never getting legally married, but finding their vows to each other sufficient in a

ceremony that’s spiritual but not “religious”.

It’s a curiously progressive stance that’s perfectly in sync with

Jessica’s surprisingly adult torch song of non-conformity and sensory awakening

“My World Is Beginning Today” (which also indulges in some heavy abstract

animation, very unusual for these kiddie specials). Her voice was done by Robie Lester, who only

has a handful of credits but, curiously enough, did provide the singing voice

for both of Eva Gabor’s Disney flicks: The Aristocats (1970/Reitherman) and The Rescuers (1977).

I’ll admit that I liked the rudimentary but charming

animation style as a kid, and it served as my first introduction to quite a few

classic film stars: Jose Ferrer and Greer Garson (The Little Drummer Boy, 1968),

Shirley Booth and Dick Shawn (the latter as the hilarious Snow Miser in The

Year Without a Santa Claus, 1974), and Jimmy Durante (the cel animated Frosty the

Snowman, 1969). Mickey Rooney--another legend

one suspects has a stamp in his future--played Santa in both SCIC2T and Year

Without...

But even memories of some of the more obscure specials

linger. Nestor, the Long-Eared Donkey

(essentially, a Biblical Rudolph from 1977) had a four-legged parental death that moved

me far more than Bambi’s mom did. Jack

Frost (1979) was a primer in how a girl can say she loves you but not, you know,

love-loves you (leaving the title character in a bittersweet frozen

friendzone). And the awkward, skeptical,

bespectacled kid mouse in Twas the Night Before Christmas (1974) was easily relatable

given what I saw in the mirror every day.

Perhaps the best loved holiday special is the one that got a

stamp this year: A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965/Melendez), which is celebrating its 50th

Anniversary. The Charles

Schulz museum in Santa Rosa, CA, isn't far from where I live and well worth the visit. It always has wonderfully-curated collections that show how savvy he was in observing human behavior through

these kids who always had childish impulses and very adult sensibilities. The TV special is no different in its critique

of commercialism at the expense of more simple and compassionate priorities (and all with

a terrific Vince Guaraldi score).

Personally, my favorite remains How the Grinch Stole

Christmas (1966 and my first exposure to Boris Karloff) so if these TV specials are a

trend with the USPS, I hope it gets an issue next--though as you can see, Dr.

Seuss has gotten a few stamps from them already.

Santa from the Rudolph issue is Scott #4948. The original Peanuts stamp is #3507 while Charlie Brown w/his tree is #5021. Dr. Seuss is #3585, "The Cat in the Hat" #3187h and "Fox in Socks" #3989. Paul

Newman is Scott #5020 and the skyskraper

stamp (#4710n) is from the Earthscapes issue. 101 Dalmatians and Lady and the Tramp are #4342 and #4028 respectively. And Elvis is Scott #5009.

My 10 Favorite Fred Astaire films

1. Shall We Dance (Sandrich, 1937)

2. Swing Time (Stevens, 1936)

3. You Were Never Lovelier (Seiter, 1942)

4. Top Hat (Sandrich, 1935)

5. The Band Wagon (Minnelli, 1953)

6. Easter Parade (Walters, 1948)

7. Follow the Fleet (Sandrich, 1936)

8. Royal Wedding (Donen, 1951)

9. Silk Stockings (Mamoulian, 1957)

10. Funny Face (Donen, 1957)