For practically as long as I can remember movies, I have known and adored Claude Rains.

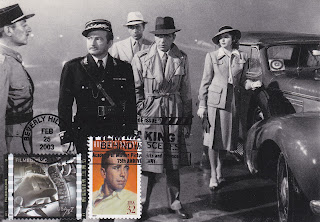

Probably the first movie I really fell in love with was Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942), and in a movie teeming with wonderful characterizations, Rains’s Renault stood out as enormously appealing and inscrutable, perhaps the best thing in an irresistibly fine film. While the rest of the characters seemed designed to fulfill their specific destiny, all the real crucial choices in the film are Louis’, and it’s his arc of redemption that sells the film, making Rick’s sacrifice satisfying because with nobility comes camaraderie. The term "bromance" didn’t exist when I was in elementary school, but this was the perfect balance of admiration, acceptance, and loyalty—two cynics who are up to the challenge when their self-interest is superseded by something greater.

Casablanca is rich with broad strokes of romance, nationalism, and honor, so it’s up to Rains to provide any real complexity. Even after multiple viewings, his motives are never obvious, his allegiances seemingly open and yet always suspect. While Rick revels in mystery, throwing out opaque answers and assertions of indifference, Renault is always plain-spoken—about his affections, his corruption, and his obvious delight in straddling every fence he can. He plays both ends against the middle down to the very last scene and Rains makes his character so amused by his own self-awareness that the character is instantly likeable even when far from respectable.

But that was classic Rains. In The Adventures of Robin Hood (Curtiz/Keighley, 1938), Basil Rathbone’s (wonderfully portrayed) villain is so miserable in his seriousness, while Rains’s Prince John relishes every syllable that he utters. In Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Capra, 1939), his Senator Paine is a realist, and while he’s positioned as the antagonist, he’s not a one-dimensional bad guy. In fact, he’s a model of networking and backroom compromise, and with our current political landscape of brinksmanship and line-in-the-sand thinking, is his type any less palatable than a Jefferson Smith?

But he could be enormously touching, too. Witness his psychiatrist in Now, Voyager (Rapper, 1942) or the loving husband in Mr. Skeffington (Sherman, 1944), turning in incredibly compassionate performances that ground these “chick flicks” in a generous emotional authenticity that’s never maudlin. In Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), he may be the villain, but compared to mercenary Cary Grant and compromised Ingrid Bergman, he comes across as surprisingly sympathetic…for a Nazi. Just because he was short doesn’t mean he couldn’t control the room (Exhibit A: They Won’t Forget—LeRoy, 1937), but Rains could also use his size to convey a weakness or moral temerity, and his Alexander Sebastian is a man clearly in over-his-head, terribly pliable by the forces of love and fear that control, and eventually doom, him. His last scene is as shattering as anything he ever did.

In short, he was usually the best thing in the movies he worked on, and given his filmography, that’s high praise indeed. Even late in his career, he steals every scene he’s in in Lawrence of Arabia (Lean, 1962). It isn’t until the desert that O’Toole really blooms, so Rains’s world-weary diplomat Dryden is the one character who has the big picture in mind, standing on the outside looking in, with bemused skepticism at the posturing from all sides.

I hope he gets a stamp one day, perhaps part of a 20-pane sheet devoted to cinema’s great character actors (joining Agnes Moorehead, Walter Brennan, Thelma Ritter and many more). The closest he ever came was missing the cut with the Universal Monsters release, since his first film was The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933). But even then, he wouldn’t have really been depicted (we never see his features in the film; his voice does all the acting)--just a bandaged head and mask, the ultimate chameleon who could blend into any situation and a memorable introduction to a tremendous career.

The Bogart, Hitchcock and Grant stamps are part of the Legends of Hollywood series (Scott #’s 3152, 3226, & 3692 respectively). Erich Wolfgang Korngold was part of the film composers series (Scott #3344) while Green Arrow (Scott #4084d) was part of the DC Comics release. The American filmmaking series provided the Film Editing stamp (Scott #3772h).

This post is part of the TCM Summer Under the Stars blogathon. Be sure to check out all the stellar entries.

Sunday, August 5, 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)